interview with Mertelj Vrabič and Vidic Grohar architects

Venice Architecture Biennale 2023: The Slovenian Pavilion returns this year with a bold quest — to unpack the issue of ecology and its defining role in shaping the development of architecture over the past decade. Curated by studios Mertelj Vrabič Arhitekti and Vidic Grohar Arhitekti, the pavilion particularly explores how ecology is most often understood as ‘energy efficiency’ or, better yet, as the technology hidden between the walls. In search of a new vocabulary and an alternative to existing building systems, the curators, together with fifty European architects and creatives, researched and analyzed examples of vernacular buildings from Europe that – unlike current contemporary practice – address ecology holistically, as an integral part of the architectural design and a living example of energy principles that are relevant to the present time.

On this occasion, designboom speaks with the curators to further uncover the Slovenian Pavilion’s spatial experience and share some surprising findings that have emerged from their quest for a new understanding of ecology in architecture. Read the full interview below.

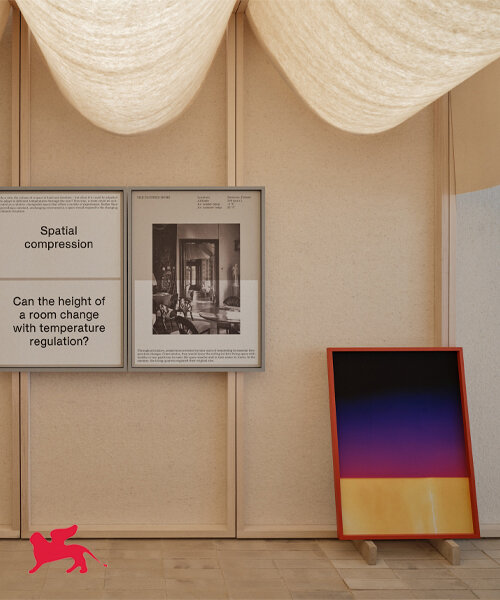

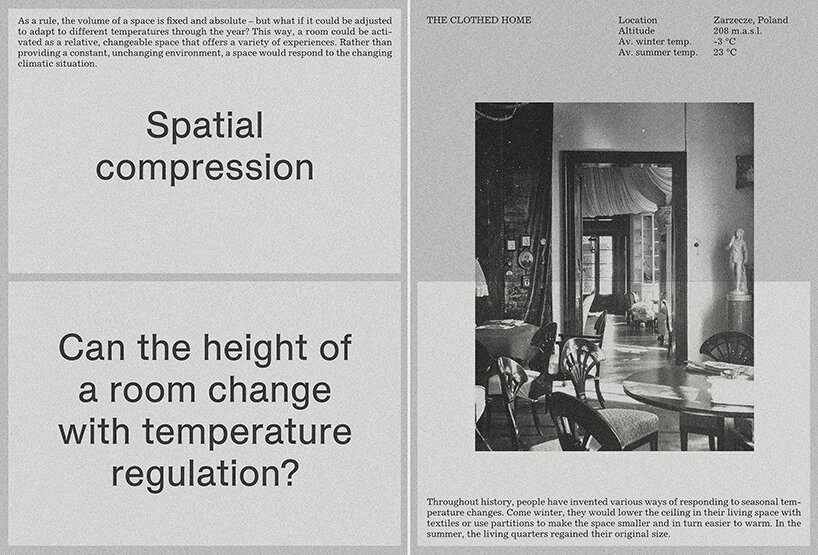

+/- 1°C | In Search of Well-Tempered Architecture: Slovenian Pavilion, installation view

image © Klemen Ilovar | @klemen_llovar

unpacking the slovenian pavilion design and theme

designboom (DB): Walk us through the spatial experience and design of the Slovenian Pavilion.

Mertelj Vrabič Arhitekti & Vidic Grohar Arhitekti (MVA & VGA): The Slovenian Pavilion project, curated and designed by architects Jure Grohar, Eva Gusel, Maša Mertelj, Anja Vidic, and Matic Vrabič from the Mertelj Vrabič Architects and Vidic Grohar Architects studios, deals with ecology in architecture. It is a 1:1 scale spatial installation in the Arsenal in Venice. The pavilion is an expression of the five energy principles developed herein: Room Within a Room, Hotspot, Intermediate Zone, Cocoon, and Spatial Compression. The pavilion also showcases more than 50 vernacular case studies contributed by various invited European architects and other creatives. The intervention consists of two primary elements constructed from natural materials: the walls and ceiling assembled from wooden frames with a swath of wool felt stretched between them, and the brick floor. Designed with the pavilion’s post-exhibition ‘second life’ in mind, the structure allows for simple disassembly and reuse at another location.

The specific materialization of the principles developed here results from the pavilion’s constructional logic – what grows up from the ground is built in brick, and what is suspended from the ceiling or continues as a wall is made of wooden frames covered with felt. The resulting space is a series of energy principles materialized in diverse environments with a strong material identity and takes on the appearance of an unconventional, abstract dwelling space. By translating those principles that are otherwise characteristic of vernacular architecture into a concrete space, the pavilion reflects on how they might be applied in contemporary living environments or the design of contemporary architecture. The pavilion, with its material presence and atmosphere, functions as an immersive space that initially communicates with the visitor on an experiential level.

Spatial Compression | image © Klemen Ilovar

DB: In what ways does it respond to this year’s Biennale theme, The Laboratory of the Future?

VGA & MVA: The curator of this year’s Architecture Biennale, Scottish-Ghanaian architect Lesley Lokko, titled the biennale with a speculative title, ‘Laboratory of the Future.’ However, many national pavilions added a third component to the equation of present-future: the past. Thus, despite the distinctly futuristic title, the importance of heritage, knowledge, skills, and practices from the past for the present and future is highlighted. This year’s Slovenian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale also explores the relationship between the past, present, and future. More precisely, the pavilion looks to the past to shed light on the connection between contemporary architecture and ecology. In doing so, it raises the question of what we understand today by the often overlooked and overused term ‘ecological’ in architecture. We highlight the question: how can architecture create its own ecology and establish a positive relationship with its environment, to which it is inherently connected?

Room within a Room | image © Klemen Ilovar

a long-awaited collaboration for the venice biennale 2023

DB: As curators of the pavilion, talk to us about the collaboration between both your studios. What were the highlights and/or challenges? How did your individual approaches and expertise complement one another?

VGA & MVA: We had considered working together several times in the past. As friends, we discuss architecture in our private gatherings regularly. We have often wondered how, as architects, we could distance ourselves critically from architectural practice—both our own and in general—not only through conversation but also through a concrete, built architectural object that reflects the initial thesis. When the open call for the Slovenian pavilion was announced, we decided it was a great opportunity to use architecture to communicate our potential thesis to the wider public. That’s why, from the very beginning, when we had just entered the open call, it seemed important to us that our intervention should be small architecture, i.e., a spatial intervention. In this project, unlike the ‘usual’ office practice, we discussed and worked at a horizontal level. Thus, a way of discussing and organizing had to be developed, which, in a few months, resulted in a clear and coherent concept and the resulting project.

Five people with different (and partly also similar) interests and perspectives have put together a multifaceted project that we believe reflects a potentially productive critique of the relationship between contemporary architecture and ecological problems: a wide network of different participants, the pavilion as an architectural project, a publication that will be published soon, and even some pieces of furniture that round off the presentation that is the Slovenian pavilion.

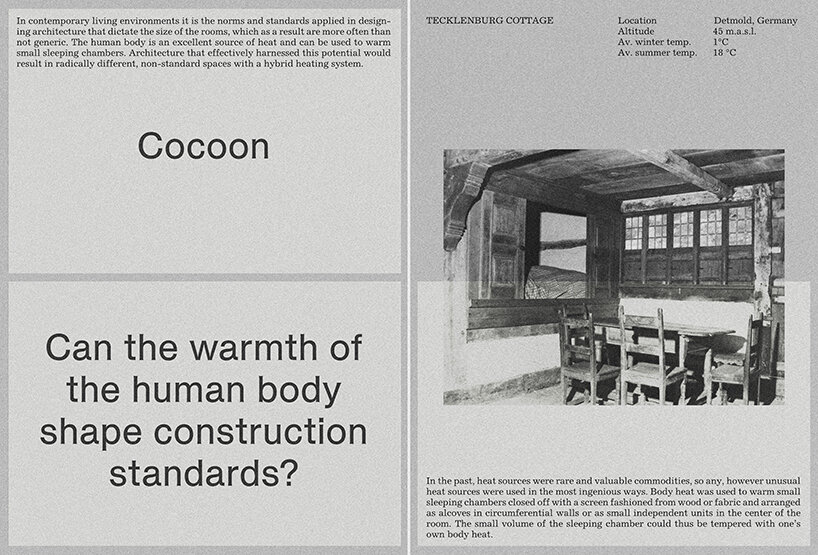

Cocoon | image © Klemen Ilovar

exploring ecology in architecture using five energy principles

DB: We were particularly intrigued by the questions displayed across the Slovenian Pavilion, one of which explores the relationship between human body warmth and construction standards. How did you go about outlining these interrogrations and what surprising answers and findings can you share with us?

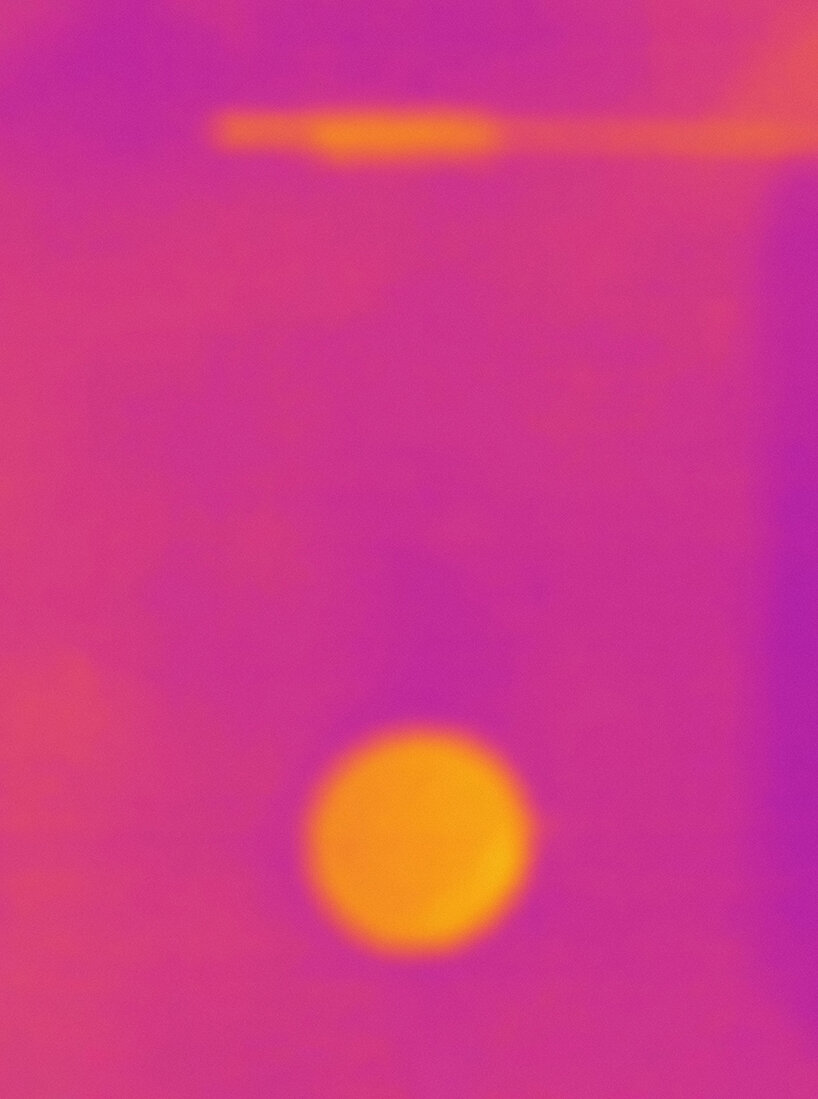

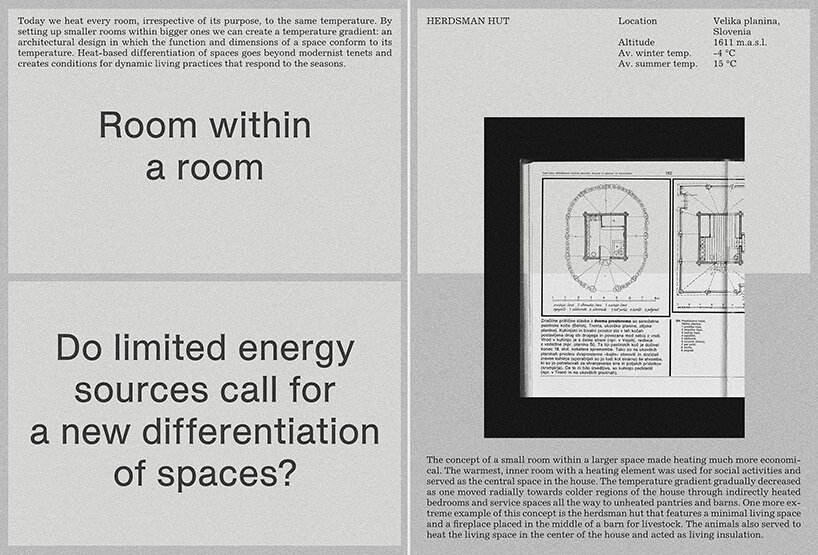

VGA & MVA: In the pavilion, we presented five out of thirteen energy principles: Room within a Room, Cocoon, Intermediate Zone, Hot Spot, and Spatial Compression. Each principle was illustrated in two ways: through a historical example of vernacular architecture and a thought-provoking question that brought the energy principle into the context of the present day. Our intention with these questions was to initiate discussions about the contemporary significance of these energy principles and their potential roles in modern architecture.

One of the principles, the Cocoon principle, raised the poignant question: Can the warmth of the human body shape construction standards? This concept stems from the historical use of heat sources, which were scarce and precious commodities in the past. People ingeniously used various heat sources, even unconventional ones, to create warmth. For instance, body heat was harnessed to warm small sleeping chambers, often enclosed with wooden or fabric screens and situated as alcoves in the surrounding walls or as separate units within a room. These small chambers could be heated using one’s own body heat. However, in contemporary living environments, architectural norms and standards typically dictate room sizes, resulting in more generic spaces.

Room within a Room, visual essay with thermal camera | image © Klemen Ilovar

While the human body is an efficient source of heat and could effectively warm small sleeping chambers, these simple solutions are often incompatible with modern standards and are rarely applied in the design of public housing. Architecture that fully utilizes this potential would create radically different, non-standard spaces with a hybrid heating system. Such an approach would require a reevaluation and rethinking of rigid construction standards. It may even be more ecological to construct smaller spaces within larger ones, even if these smaller spaces only accommodate a single bed. This diversity in dimensions and solutions could offer advantages that current building codes and construction standards do not permit. Additionally, our exploration extended beyond the relationship between human body warmth and architecture; we also considered the connection between animal body heat and architecture.

A fascinating vernacular example illustrating the energy principle of Room within a Room is the herdsman hut on the mountain pasture of Velika Planina. In this concept, a small room within a larger space significantly improved heating efficiency. The herdsman hut features a minimal living space with a fireplace situated in the middle of a barn for livestock. The animals thus served to heat the central living space and also acted as living insulation.

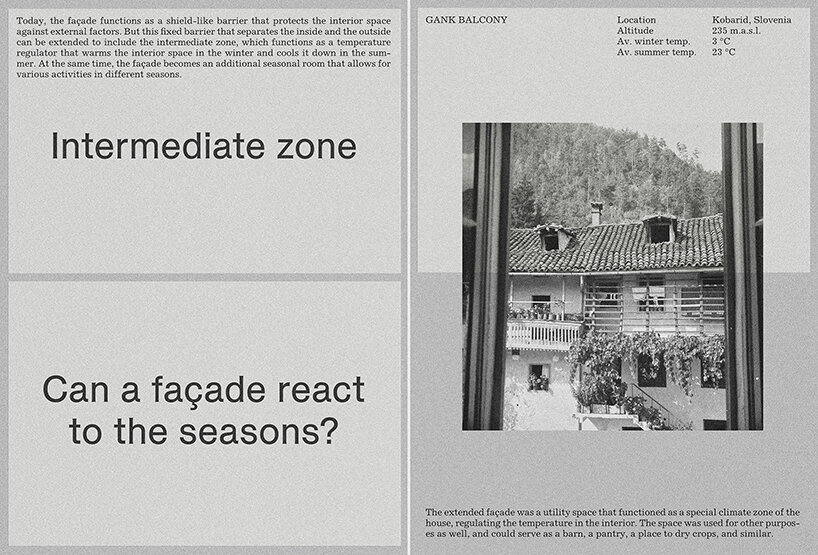

Intermediate Zone | image © Klemen Ilovar

DB: Did the research findings make you re-evaluate your own approach to architecture? If so, how?

VGA & MVA: With this project, we found ourselves in a situation where we could think freely about architecture and its most important contemporary challenges. We operated in a way different from a ‘standard’ architectural project, and in doing so, we developed a more programmatic thesis through the project’s evolution. In the research that led to the presentation in the pavilion, we developed the idea of energy principles – possible approaches to addressing environmental issues both technically and architecturally. These approaches involve new typological and material solutions and the integration of technological and spatial elements that articulate a potentially different contemporary architecture. This goes beyond simply adding technological layers such as insulation, improving windows, or relying on air-conditioning. The necessity of addressing environmental issues in an alternative architectural way is the most important lesson that we, as well as other architects, can apply to our thinking and the design of our projects.

Cocoon, energy principle | image courtesy the curators

DB: In today’s world, how can we balance vernacular and intuitive architecture with modern technologies?

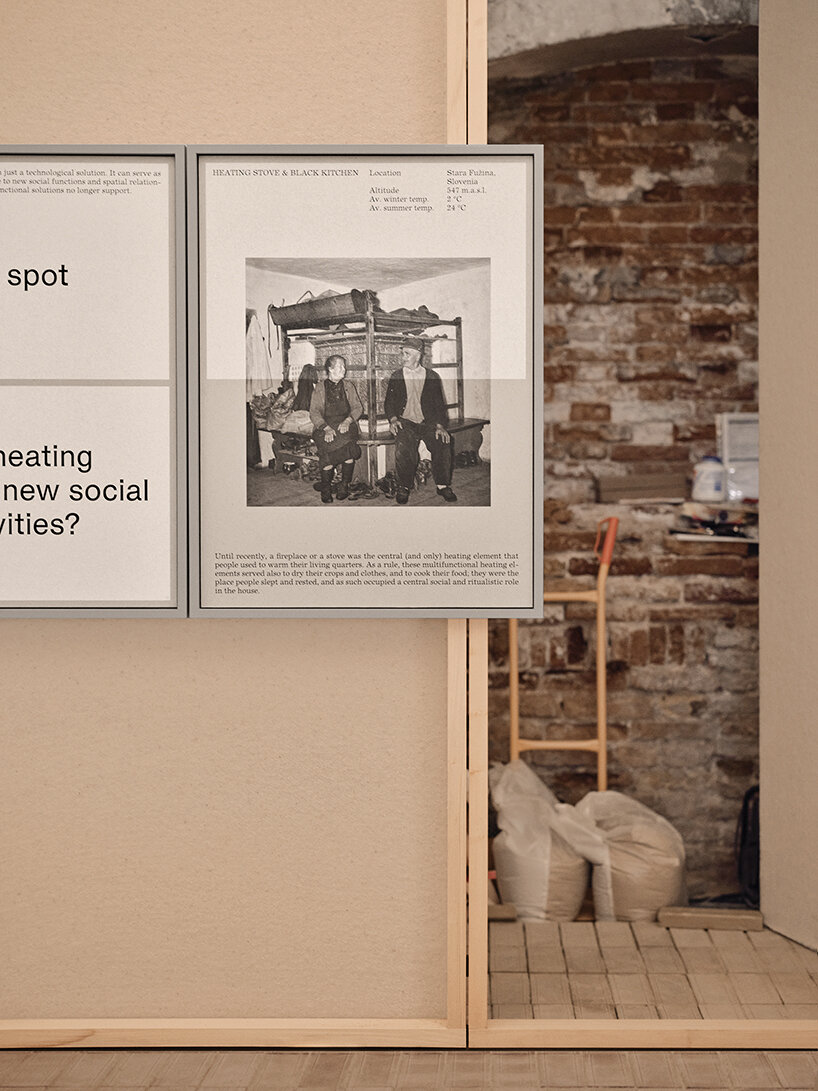

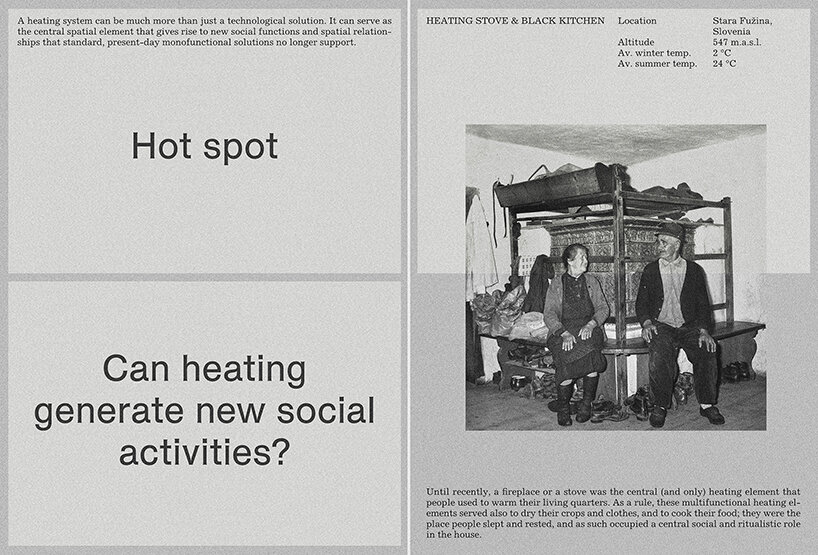

VGA & MVA: Integrating technology with architecture is crucial for achieving coherence. Otherwise, we have technology and architecture existing as separate entities. One of the energy principles we presented at the Biennale, which we named ‘Hot Spot,’ vividly illustrates this concept. Here, we posed the question: Can heating generate new social activities? In the past, people typically used fireplaces or stoves to heat their living spaces. These multifunctional heating elements provided warmth and served to dry crops and clothes and cook food. They were hubs where people gathered during the day and slept at night, relishing the lingering warmth after the heating device had cooled down. Consequently, these heat-generating devices became generators of social activity and daily rituals within the household. Thus, the heating system can be more than just a technological solution; it can serve as the central spatial element that nurtures new social interactions and spatial relationships—elements that contemporary standard, monofunctional solutions often overlook.

Another important and readily achievable solution lies in the necessary shift in behavior and mindset. Today, we are accustomed to maintaining uniform temperatures in all rooms, preferably at or above 22 °C, and wearing T-shirts indoors during the winter. This practice, a contemporary phenomenon, doesn’t align with the physiological needs of our bodies. If rooms were heated differently based on their use, creating a temperature gradient within the home, it would not compromise comfort and would lead to significant energy savings.

Spatial Compression, energy principle | image courtesy the curators

concluding thoughts

DB: Building on your re-examination of ecology, the word ‘sustainability’ has gotten its fair share of criticism. Many experts argue that it has been corrupted and tossed around for political and corporate interest, rendering it ‘meaningless’ in some cases. What are your thoughts on that? And how would you define sustainability?

VGA & MVA: This is true. The key question we are raising is whether ecology can be (re)thought through architecture and how it can productively serve architecture – and, by extension, us and our planet. In other words, we try to bring ecological issues back to the domain of architecture and discuss them through the building design. The exhibition and accompanying catalog thus re-examine not only the established concepts but also the vocabulary associated with ecology in architecture. Instead of the ubiquitous phrase ‘energy efficiency,’ we, therefore, use the word ‘ecology’: we understand it as the multiple and complex relationships between architecture and its environment that go beyond the use of technology.

Such an inclusive role of ecology in architecture also transcends the meaning of another universally (over)used word – the word ‘sustainability,’ which you have already mentioned and which reflects the idea of the sustainment and preservation of the current situation, or as philosopher Timothy Morton suggests in his book Hyperobjects: ‘What exactly are we sustaining when we talk about sustainability? An intrinsically out-of-control system that sucks in grey goo at one end and pushes out grey value at the other.’ The word ‘ecology’, on the other hand, evokes an idea of relating architecture to its environment much more horizontally and takes a much wider perspective on what we do and make.

Hot Spot, energy principle | image © Klemen Ilovar

DB: In light of the insights you’ve gained from this project, what lessons would you share with / what advice would you give young architects entering the professional sphere?

VGA & MVA: A young architect is continually seeking a professional orientation and ultimately, an architectural language that mirrors their vision. The matter of ecology can serve as a significant starting point for practicing architects to shape their architectural production and actively contribute to a more environmentally conscious society. Ecology has become so integral to our everyday lives that addressing it has grown increasingly important, necessitating changes in numerous aspects of our reality. Architecture offers one of the potential avenues through which we can make these necessary changes and contribute to a more sustainable and environmentally conscious way of living.

installation view at the Slovenian Pavilion | image © Klemen Ilovar

Curators Eva Gusel, Jure Grohar, Maša Mertelj, Matic Vrabič, Anja Vidic | image © Klemen Ilovar

project info:

name: +/- 1°C | In Search of Well-Tempered Architecture

location: Pavilion of Slovenia | @slovenianpavilion, Arsenale, Venice

curators: Jure Grohar, Eva Gusel, Maša Mertelj, Anja Vidic, Matic Vrabič

pavilion design: Mertelj Vrabič Arhitekti | @merteljvrabic, Vidic Grohar Arhitekti | @vidicgrohararhitekti

commissioner: Maja Vardjan

commissioner’s assistant: Nikola Pongrac

graphic designer: Žiga Testen

collaborators: Elvis Jerkič, Vanesa Maček, Josipa Regović

production: Museum for Architecture and Design Ljubljana (MAO)

program: La Biennale di Venezia | @labiennale

invited participants: Anna Bach, Eugeni Bach (A&EB architects); Marcello Galiotto, Alessandra Rampazzo (AMAA); Urban Petranovič, Davor Počivašek (Arhitekti Počivašek Petranovič); Niklas Fanelsa (Atelier Fanelsa); Alicja Bielawska, Simone De Iacobis, Aleksandra Kędziorek, Małgorzata Kuciewicz; Laura Bonell, Daniel López-Dòriga (Bonell+Dòriga); Radim Louda, Paul Mouchet (CENTRAL offau); Velika Ivkovska; KOSMOS; Aidas Krutejavas (KSFA Krutejavas Studio For Architecture); Laura Linsi & Roland Reemaa (LLRRLLRR); Benjamin Lafore, Sébastien Martinez-Barat (MBL architectes); Ana Victoria Munteanu, Daniel Tudor Munteanu; Daniel Norell, Einar Rodhe (Norell / Rodhe); Søren Pihlmann (Pihlmann architects); Ambra Fabi, Giovanni Piovene (Piovenefabi); Matteo Ghidoni (Salottobuono); Gordon Selbach; Pablo Canga, Ana Herreros (SOLAR); Elena Schütz, Julian Schubert, Leonard Streich (Something Fantastic); Jakob Sellaoui (Studio Jakob Sellaoui); Hana Mohar, Frane Stančić (Studio Ploca); Susanne Brorson (Studio Susanne Brorson); Benjamin Gallegos Gabilondo, Marco Provinciali (Supervoid); Ana Kreč (Svet vmes); Janja Šušnjar; Mireia Luzárraga, Alejandro Muiño (TAKK); Léone Drapeaud, Manuel León Fanjul, Johnny Leya (Traumnovelle); Gaetan Brunet, Chloé Valadié (UR); Javier García-Germán (TAAs)

ARCHITECTURE INTERVIEWS (253)

VENICE ARCHITECTURE BIENNALE 2023 (40)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.